24

ISSUES: Racial & Ethnic Discrimination

Chapter 1: Racism & discrimination

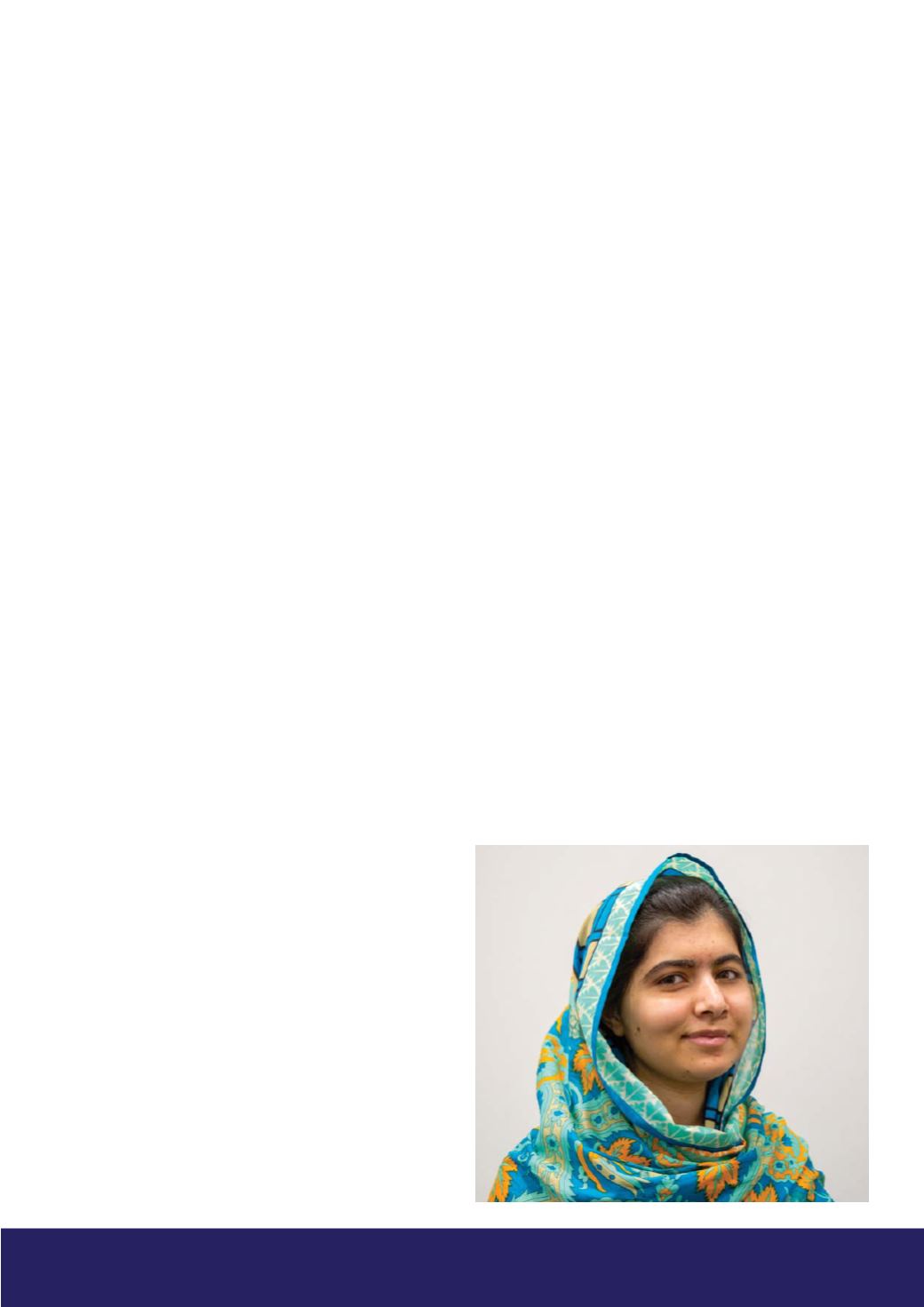

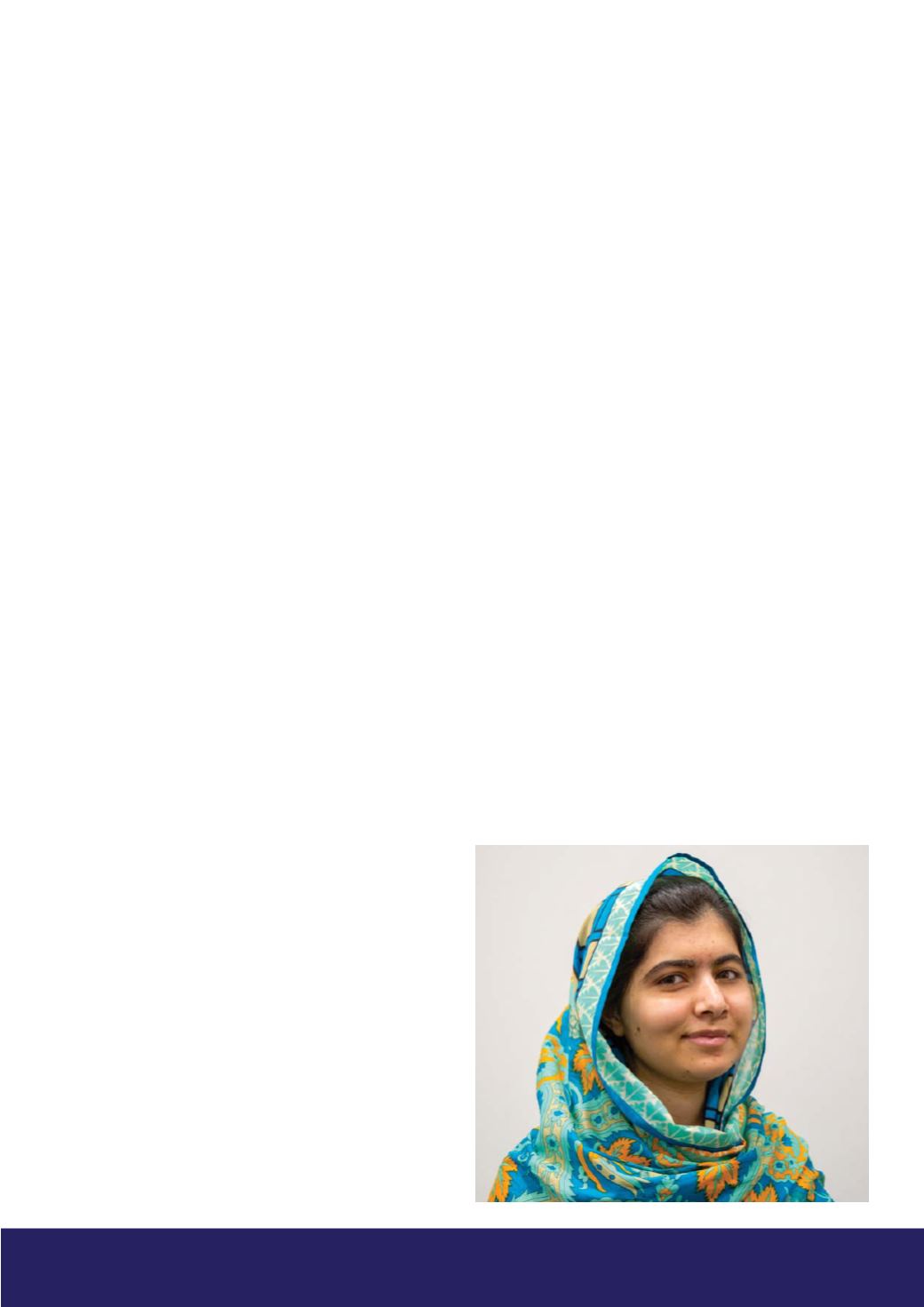

Racist and sexist assumptions endured in UK

media coverage of MalalaYousafzai

A

new study has found that seemingly positive media

coverage of feminist campaigner Malala Yousafzai

is actually full of patronising assumptions about

women in Muslim countries.

The study analysed more than 140,000 words of coverage of

activist Yousafzai in the nine months after she was attacked

by the Pakistani Taleban. It found the fearless and eloquent

campaignerwas reduced toapassive victimby theBritishmedia.

In some cases, she was simply referred to as “Shot Pakistani Girl”.

The study was carried out by Rosie Walters, a postgraduate

researcher at the University of Bristol’s School of Sociology,

Politics and International Studies. She said: “The West has often

been guilty of portraying women in Muslim countries as passive

and as victims. Malala Yousafzai challenges that stereotype in

every way, which is why I wanted to analyse the coverage of her.

“She even said herself that she doesn’t want to be portrayed

as the young woman who was shot by the Taleban, but rather

as the young woman who bravely fought for her rights. Sadly,

the findings of this study show that the British media is far from

granting that request.”

The research, published in

The British Journal of Politics and

International Relations

, used a form of discourse analysis that

analyses thewords andterms associatedwithaparticular subject

(in this case both Malala Yousafzai and her native Pakistan), the

assumptions that have to be made for these associations to

make sense, and the way in which these assumptions position

subjects in relation to one another.

Walters’ research found that in more than 140,000 words in

The Daily Mail

,

The Guardian

,

The Independent

,

The Sun

and

The

Telegraph

, the word feminist was used just twice, and on neither

occasion to refer to Yousafzai, despite her tireless campaigning

for the rights of girls and young women. The underlying

assumption this demonstrates is that a Pakistani woman cannot

be a feminist.

“The coveragepositions theUKas inherently superior toPakistan

because it has supposedly already achieved gender equality,”

saidWalters.

“Yet it simultaneously shows that this is far from true. One article

even advised Yousafzai on how to dress and behave in her new

school inBirminghamso she doesn’t come across as toomuchof

a geek. It seems astonishing that a youngwomanwhohas come

within centimetres of losing her life fighting for her right to an

education is being advised to tone down her ambition, in case it

makes her seemuncool or unattractive to boys.

“If anything, it suggests that Malala Yousafzai has a great deal

she could teach us about fighting to be judged on one’s intellect

and abilities, and not on gender.”

Another interesting contradiction the research identified was in

media coverage of Yousafzai’s move to the UK, and the medical

treatment she received here. While all five newspapers were

quick to express pride in the NHS care that she received, they

were also keen to emphasise that all her expenses would bemet

by the Pakistani Government.

In fact, just two weeks after an article in

The Sun

proclaimed:

“…the NHS should be proud of its success in treating the brave

schoolgirl…”, the tabloid published another article with a

headline “NHS ‘too good to migrants”, claiming many doctors

were refusing to treat people who weren’t British citizens.

Walters said: “The overwhelming outpouring of support and

admiration for Malala Yousafzai in the months after the attack

represented a real opportunity to re-examine some of the

assumptions we make about Muslim women, and also about

the kind of people who migrate to the UK in search of safety.

Unfortunately, it seems that opportunity was missed.”

Although the study focuses on some individual articles to

illustrate wider trends, Walters, whose research on girlhood

and international politics is funded by the Economic and Social

Research Council, was keen to emphasise her study is not a

criticismof journalists.

“The point of the study is not about individuals and the

vocabulary they use. It’s about identifying patterns across many

different texts, which tell us a great deal about how we as a

nation represent ourselves in journalism, and how we represent

other cultures and countries.

“In this case, what it clearly shows is that in our society, it is far

easier to label Malala Yousafzai a ‘victim’ than it is to call her

powerful, a survivor, or even a feminist.”

19May 2016

Ö

The above information is reprinted with kind permission

from the University of Bristol. Please visit

for further information.

©University of Bristol 2017