2

ISSUES: Citizenship

Chapter 1: Citizenship in the UK

the extent to which shared customs and

traditions matter:

Nowwe would like to ask a few questions

about minority groups in Britain. How

much do you agree or disagree with the

following statement? It is impossible

for people who do not share Britain’s

customs and traditions to become fully

British.

Of the nine attributes we asked about,

six are seen as “very” or “fairly” important

by around three-quarters of people or

more. Themost important factor is being

able to speak English (which 95 per cent

think is important), followed by having

British citizenship and respecting Britain’s

political institutions and laws (both 85

per cent). Around three-quarters think

being born in Britain is important, but

only half that having British ancestry

matters. It is notable that only a quarter

think that being Christian is important for

being “truly British”.

If we look at the data from a historical

perspective, it is clear that, despite little

change between 1995 and 2003, there

have been some major shifts since then.

In particular, the perceived importance of

being able to speak English has increased

by nearly ten percentage points.

There has also been an increase in the

proportion who think it important that

someone has lived for most of their life in

Britain, up from 69 per cent in 2003 to 77

per cent now.

To understand how these results

correspond to the two identity

dimensions we mentioned earlier

(ethnic versus civic) we used a technique

called factor analysis. The results of

this analysis [...] show that responses

[...] do indeed divide into two different

dimensions, which correspond well with

the differences between ethnic and civic

conceptions of national identity.

We then calculated an ethnic identity

score and a civic identity score for

each respondent, based on how

they had answered these questions.

In each case, the closer the score is

to five, the more weight that person

puts on the relevant dimension of

national identity, and the closer it is

to 0, the less weight. The results show

that the vast majority of Britons do

not see whether or not someone is

“truly British” as being down to solely

civic or ethnic criteria – instead, many

see both as playing a role. Another,

smaller, group have an entirely civic

view of national identity. Almost

nobody has an entirely ethnic view.

Finally, there is also evidence of a

group whose views about national

identity have neither an ethnic nor a

civic component.

The majority of people (nearly two-

thirds) attach importance to both

ethnic and civic aspects of national

identity while about one-third tend

to think of national identity only in

civic terms. Six per cent do not appear

to think of national identity in either

ethnic or civic terms. Comparing

these findings with those from earlier

years shows considerable continuity,

although there is the hint of a small

increase in the proportion of the

population with a civic notion of

national identity, from 23 per cent

in 1995 to 34 per cent in 2003 and 31

per cent in 2013. There has also been

a small change in the proportion

who think that both civic and ethnic

aspects of national identity matter:

after a four percentage point dip

between 1995 and 2003, by 2013 this

proportion had returned to its 1995

level of 63 per cent.

Of course, these overall findings

are likely to mask considerable

differences

between

particular

groups. An obvious starting point

here is age; we know from earlier work

that there are clear age differences in

national pride, with younger groups

being less likely than older ones to

express pride in being British (Young,

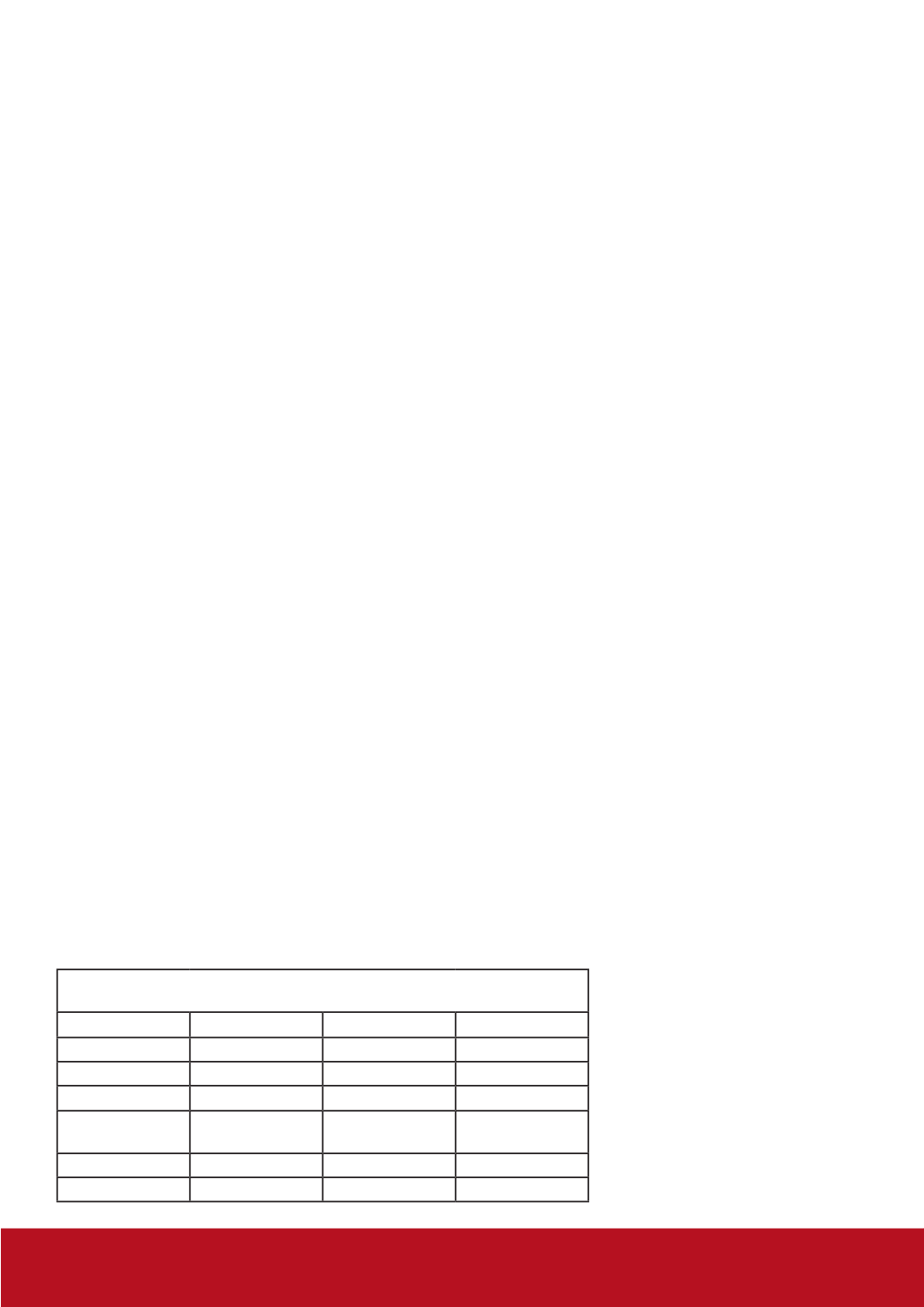

2014). We explore this in Table 4.5.

However, rather than focusing on

age, we examine the views of specific

generations as there are strong

reasons to suspect that their different

experiences during their formative

years (particularly in terms of their

exposure to war and conflict) will have

had an impact on the way they think

about Britain and British identity.

To do this we pooled together our

2003 and 2013 findings (to increase

the sample size available for analysis)

and then allocated people into one of

three different generational groups:

those born before 1945; those born

between 1945 and 1964; and those

born after 1964. The results show

that there are indeed considerable

generational differences; nearly nine

in ten of the pre-1945 generation

have a civic and ethnic view of British

national identity, but the same is

only true of six in ten of those born

between 1945 and 1964, falling to

five in ten among the youngest

generation. Conversely, while 40 per

cent of those born after 1964 have a

view of British national identity based

only on civic factors, this is true of just

13 per cent of those born before 1945.

These findings suggest that, over

time, the importance attached to

ascribed ethnic factors in thinking

about national identity may well

decline, as older generations die out

and are replaced by generations who

are less likely to think of Britishness as

dependent on factors such as birth,

ancestry and sharing customs and

traditions.

2014

Ö

The above information is reprinted

with kind permission from NatCen

Social Research. Please visit www.

bsa.natcen.ac.uk

for

further

information.

©NatCen Social Research 2017

Table 4.5 Distribution of conceptions of national identity, by generation, 2003

and 2013

Born pre- 1945 Born 1945–1964 Born post- 1964

%

%

%

Civic and ethnic 86

61

50

Only civic

13

33

40

Neither civic nor

ethnic

2

5

10

Weighted base

341

591

737

Unweighted base 408

588

663