ISSUES

: Our Changing Population

Chapter 2: Global population issues

26

high temperatures and pressures. All that heat requires

serious amounts of energy, and the hydrogen is derived

from natural gas, which currently means the Haber

process uses lots of fossil fuels. If we include production,

processing, packaging, transportation, marketing and

consumption, then the food system consumes more

than 30% of total energy use while contributing 20% to

global greenhouse gas emissions.

Feeding the next four billion

If industrialised agriculture can now feed seven billion,

then why can’t we figure out how to feed 11 billion by

the end of this century? There may be many issues that

need to be addressed, the argument runs, but famine

isn’t one of them. However, there are a number of

potentially unpleasant problems with this prognosis.

First, some research suggests global food production

is stagnating. The green revolution hasn’t run out of

steam just yet but innovations such as GM crops, more

efficient irrigation and subterranean farming aren’t

going to have a big enough impact. The low-hanging

fruits of yield improvements have already been gobbled

up.

Second, the current high yields assume plentiful and

cheap supplies of phosphorus, nitrogen and fossil fuels

– mainly oil and gas. Mineral phosphorus isn’t going to

run out anytime soon, nor will oil, but both are becoming

increasingly harder to obtain. All things being equal this

will make them more expensive. The chaos in the world

food systems in 2007–8 gives some indication of the

impact of higher food prices.

Third, soil is running out. Or rather it is running away.

Intensive agriculture, which plants crops on fields

without respite, leads to soil erosion. This can be offset

by using more fertiliser, but there comes a point where

the soil is so eroded that farming there becomes very

limited, and it will take many years for such soils to

recover.

Fourth, it is not even certain we will be able to maintain

yields in a world that is facing potentially significant

environmental change. We are on course towards 2ºC

of warming by the end of this century. Just when we

have the greatest numbers of people to feed, floods,

storms, droughts and other extreme weather will cause

significant disruption to food production. In order to

avoid dangerous climate change, we must keep the

majority of the Earth’s fossil fuel deposits in the ground

– the same fossil fuels that our food production system

has become effectively addicted to.

If humanity is to have a long-term future, we must

address all these challenges at the same time as

reducing our impacts on the planetary processes that

ultimately provide not just the food we eat, but water we

drink and air we breathe. This is a challenge far greater

than those that so exercised Malthus 200 years ago.

12 August 2015

Ö

Ö

The above information is reprinted with kind

permission from

The Conversation

. Please visit

for further information.

© 2010–2015, The Conversation Trust (UK)

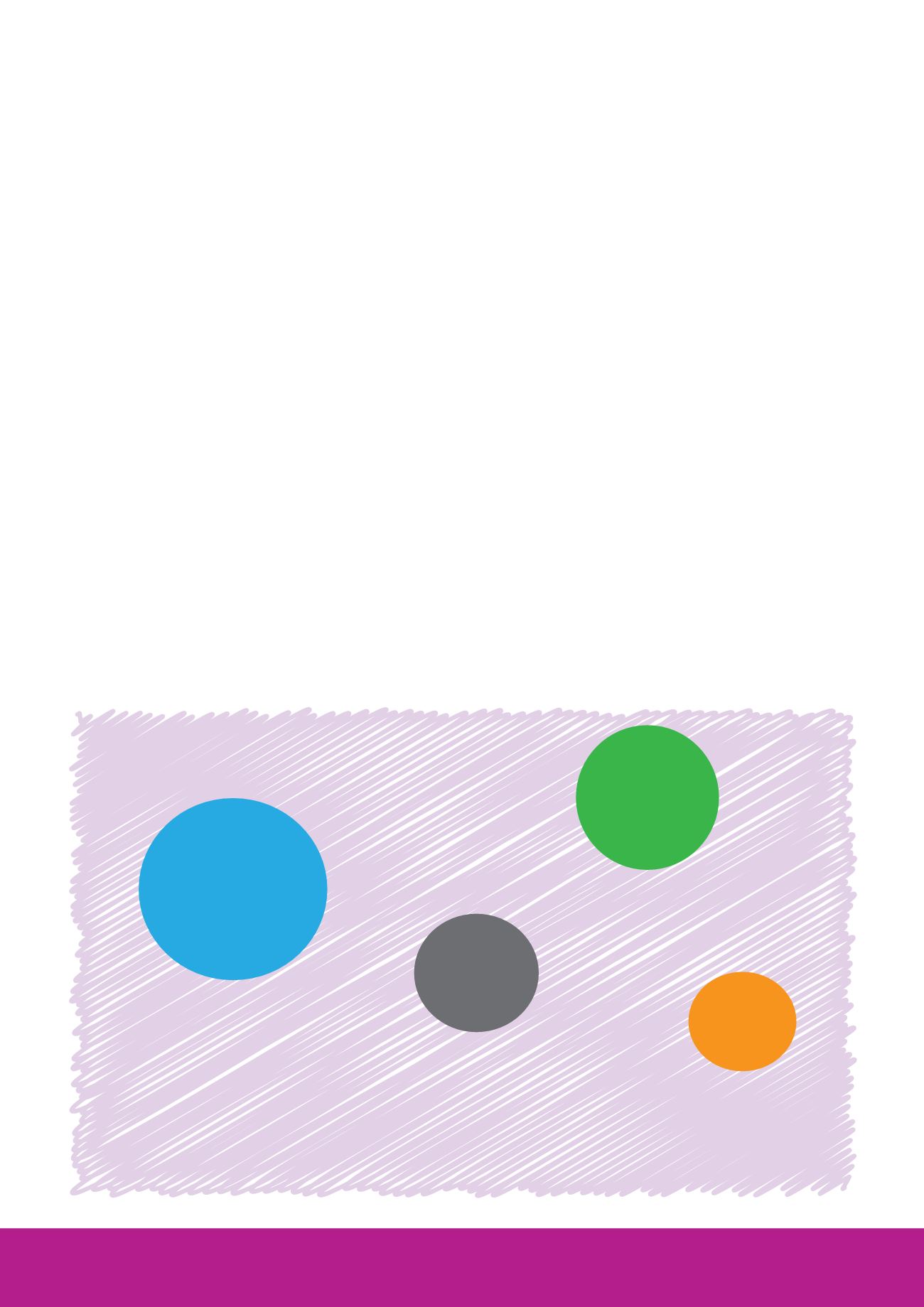

The impact of eating meat-heavy diets

Source: onegreenplanet.org/eatfortheplanet/

* The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that livestock production is responsible for

14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, while other organizations like the Worldwatch Institute have

estimated it could be as much as 51 percent.

70%

14.5%

45%

33%

Global freshwater supplies

used for agriculture

Global greenhouse

emissions

produced by livestock*

Global land

occupied by the

livestock system

Global arable

land devoted

to livestock feed